CovidSurg Research Explained

The CovidSurg group aims to understand the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on surgical patients and help surgeons and healthcare services adapt patient care to make it as safe as possible during and after the pandemic.

This page explains the CovidSurg research findings that are helping guide decisions for surgical patients and plan surgical services. The summaries in the dropdown boxes are designed to be accessible to patients, their families and the wider public audience.

The CovidSurg group has carried out two main ‘cohort’ studies tracking the outcomes of surgical patients. The first looked at patients diagnosed with COVID-19 around the time of their operation to understand their unique risks. The second is examining the outcomes for patients with cancer who have had surgery or should have had surgery if not for the pandemic. The team has also been assessing the influence of the pandemic on surgical services, including operation cancellations.

The findings of these studies are directly impacting on and informing patient health and surgical safety.

CovidSurg is committed to disseminating data quickly that can impact patient care. You can watch our Webinars here.

Planning for the Pandemic

In March 2020, the CovidSurg group started work to identify evidence and experience from other surgeons in countries already affected by the coronavirus. They identified key actions that surgical services should take to minimise the impact and enhance safety during the pandemic. A Global Guidance document was published in the British Journal of Surgery.

Context: In March 2020, surgeons worldwide urgently needed guidance on how to deliver surgical services safely and effectively during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Surgical teams needed to contribute to the COVID-19 response while continuing to care for emergency and urgent surgical patients. They needed to work with limited hospital beds, expect staff shortages and avoid the risks of in-hospital spread of the virus.

Aim: To identify key aspects of care, to safely deliver urgent surgery during the pandemic.

Strategy: First, searches were completed to find articles about management of surgical patients during pandemics. Second, surgeons and anaesthetists with first-hand pandemic experience were interviewed. Key challenges were identified and action plans proposed.

Impact: By gathering the best evidence and experiences, the study helps surgeons optimise care during the pandemic. This report helps surgical planning and promotes patient safety despite the challenging circumstances.

Results: The searches and interviews identified seven aspects of surgery that would need special attentions, to deliver safe surgery during the pandemic.

1. Planning for pandemics should be:

- Part of routine planning at hospitals.

- Led by a surgeon or anaesthetist with input from infection control experts.

- Updated regularly according to international guidelines.

- Rapidly activated when there is a pandemic threat, to quickly update hospital staff training.

2. Outpatient visits should be:

- Replaced by telephone [or video] consultations where possible.

- Postponed if care is non-urgent.

- Undertaken at a specific date and time to minimise time spent in hospital, and ONLY when a physical visit for urgent diagnostic tests or care is essential.

- Rescheduled if a patient displays symptoms of the pandemic illness.

3. Planned (Elective surgery) should be:

- Reduced to free up beds and staff to care for pandemic patients and reduce the spread of infection.

- Prioritised based on urgency and the risks to patients of any delay.

- Modified to reduce operating times.

- Postponed or if undertaken, keeping patients fully informed of benefits and risks.

- Tracked so that the backlog of operations can be undertaken after the pandemic disease peak.

4. Cancer care should be:

- Delivered carefully keeping in mind the risks of the disease worsening.

- Continued as long as safely possible, according to hospital capacity.

5. Emergency surgical care should be:

- Avoided where non-operative treatment is a reasonable option.

- Undertaken with caution, due to the risks of complications and death if patients become infected with the virus. Only urgent, unavoidable surgery will go ahead.

- Delivered by surgeons trained to

- recognize possible COVID-19 infection.

- test appropriately.

- wear personal protective equipment to protect patients and themselves.

- Delivered to patients with suspected or confirmed infection

- in separate units.

- with specific logistics planning for transfer between departments.

- in an allocated operating theatre for COVID-19 positive patients.

- Undertaken away from parts of the hospital caring for patients with COVID-19.

6. Patients with complications of COVID-19 after surgery should be:

- Anticipated;

- patients may have been in contact with the virus before, during or after their operation.

- they may start showing symptoms while recovering.

- they are more likely to become seriously ill if they get the virus.

- Tested for the virus.

- Isolated to stop virus spreading.

- Cared for by specific team members.

- Discharged home with clear instructions about how to avoid spreading the virus.

7. Surgical teams should:

- Anticipate colleague sickness in their pandemic rotas.

- Maintain social distancing.

- Adopt teleconferencing in place of meetings.

- Take into account colleagues at high risk who may need to shield, or with caring commitments.

Conclusion: Specific ‘pandemic-preparedness’ plans should be made in every hospital and regularly updated during any pandemic to best protect and care for surgical patients.

Having Surgery and Getting COVID-19

The first results from the ‘CovidSurg Cohort’ study, tracked the outcomes of surgical patients diagnosed with COVID-19 around the time of their operation. You can read a summary here of the first paper about death and breathing complications after surgery in patients infected with coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2). The paper was published in The Lancet. It was a massive team effort.

Context: A new coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) appeared in late 2019, rapidly spread across the world and resulted in the COVID-19 pandemic declared by the World Health Organisation on 11th March 2020. Very little was known of the effects of the virus on surgical patients who are particularly vulnerable with risks from an operation as well as risks of infection with the virus.

Aims: To find out what happens to patients after an operation if they are infected with the virus either just before or in the first month after their operation. Specifically, we wanted to find out how many patients die after surgery, how many develop breathing complications, and identify key risk factors.

Impact: The rates of breathing complications and death associated with COVID-19 around the time of operation are important to help surgeons and patients make the safest treatment decisions.

Strategy: Surgeons from hospitals worldwide were invited to take part in this study. In 235 hospitals from 24 countries surgeons and researchers identified all patients who had an operation and tested positive for coronavirus around the time of surgery. Patients who were suspected to have the virus (but not tested) were also included as testing was not widely available in the early stages of the pandemic.

Team members collected anonymous patient data about age, gender, underlying illnesses and their operation. Patient records were followed up for 30 days after the operation. Researchers recorded if a patient had died or been diagnosed with one of three serious breathing problems: pneumonia (lung infection); unexpected ventilation (an artificial breathing machine); or acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS, where the lungs become badly inflamed and cannot provide the body with enough oxygen).

Results:

What did the study find?

1128 patients operated between 1 Jan and 31 March 2020 were included in the study. 53 percent of patients were men, and nearly 50% were 70 years or older. The majority of patients underwent emergency surgery (74%), and most had major operations (74%). About a quarter of patients had cancer surgery (24%).

· 268 of 1128 patients (23.8%) died within 30 days of their operation.

· Just over half of patients (51.2%) had serious breathing complications. In this group the death rate was much higher at 38%.

· With pneumonia, the death rate was 38%; those requiring unexpected ventilation had a death rate of 41% and in patients with ARDS, the death rate was 63%.

Who is at highest risk?

We identified patients and operation characteristics that increased patients’ risk of death. We found that male patients, age 70 years or over, those with underlying health problems; undergoing a ‘major’ operation, emergency surgery or cancer surgery all led to the higher risks of death.

What were the rates of serious breathing complications and death before the pandemic?

Patients with SARS-CoV-2 after an operation have overall, substantially higher rates of breathing problems and death than any studies have shown before the pandemic. A national audit in the UK (called ‘NELA’) looking at emergency abdominal surgery, showed 16.9% risk of death overall and 23.4% in frail patients >70years old. An international study (by GlobalSurg) in 58 low and middle-income countries showed 14.9% death rate in patients identified as high risk, after the same type of surgery. The death rates of patients with the virus after an operation are extremely high and similar to the death rates of the small group of severe COVID-19 patients who need intensive care.

Conclusion: The high risks of breathing complications and death have highlighted that surgical patients who contract coronavirus are particularly vulnerable. We recommend that surgeons ‘raise the threshold’ for surgery during the pandemic – surgeons should postpone operations or select non-operative management options where available. Furthermore strategies should be developed to reduce in-hospital SARS-CoV-2 transmission so minimising the risk of postoperative complications.

Operation Cancellations

The high rates of breathing complications and death identified among patients operated during the pandemic, who also caught the virus, supported early pandemic decisions to postpone elective surgery. However the risks of postponing tens and hundreds of thousands of operations are significant. To quantify the burden, the CovidSurg group published a modelling study in the British Journal of Surgery.

Context: COVID-19 has led to worldwide disruption to surgical services. Cancellations have expanded waiting lists and new patients continue to be added. Operations cancelled early in the pandemic had benefits in:

- Protecting patients from possible infection with COVID-19 in hospital

- Preserving precious personal protective equipment

- Releasing ventilators, ward and critical care beds for emergency care of COVID-19 patients

- Releasing anaesthetists, theatre staff and surgeons for redeployment to other departments

Aim: To estimate the expected number of cancelled operations worldwide in the peak 12 weeks of COVID-19 pandemic disruption.

Impact: This evidence can be used to assist healthcare providers plan and create strategies for surgical services in the pandemic recovery period.

Strategy: We invited surgeons from hospitals worldwide to give expert estimates of the proportions of planned (elective) surgery that would be cancelled in the peak 12 weeks of the pandemic. 359 hospitals in 71 countries took part. Data was analysed using the usual numbers of operations per country, to calculate total expected cancellations by country and specialty.

Results:

What did the study find?

- Estimates for proportions of cancelled surgery were highest for benign (non-progressive or non-cancerous) conditions (71-87% cancelled).

- The proportion of cancelled cancer surgery was lowest in the most developed countries. There was a wide range in rate of cancer surgery cancellations, (23-77%).

- Planned obstetric operations were cancelled in 17-38%.

What does that mean in real numbers?

- Approximately 28.4 million operations were cancelled in the peak 12 weeks of the COVID-19 pandemic, that is 2.4 million per week.

- In 11 countries, >50,000 operations were cancelled per week.

- Of the cancellations, we estimate:

- >90%, 25.6million were for benign disease

- 8%, 2.3million were for cancer

- 1.6%, 0.4million were for obstetrics.

- Orthopaedic surgery was most frequently cancelled.

- Results were broken down to country-level. The most cancellations were predicted in Europe and Central Asia where there is normally higher surgical activity. The least in Sub-Saharan Africa.

- Estimates for least to worst case disruption reported 20-44million cancellations.

What will this mean going forward?

If surgical services increased activity by 20% above pre-pandemic levels they would take 45 weeks (>10 months) to clear the backlog of operations.

How accurate are these estimates?

Surgeons in countries that had not yet reached pandemic peak reported expected proportions of cancelled surgery.

Results are presented with best and worst case disruption scenarios.

This study uses published estimates of the number of operations that take place per country if that country does not publish data.

If regional outbreaks last longer or shorter than 12 weeks, estimates may not match local disruption but can be adjusted to aid recovery planning.

Conclusion: To clear growing waiting lists for surgery, there will need to be significant government investment. For example, in the UK the operation backlog would cost >£2billion to clear (based on £4000 per operation).

While patients await surgery, they risk worsening disease. This may result in patients being unable to work, which would further increase the costs of the pandemic to society.

If future COVID-19 outbreaks occur, surgical services should be ready to continue to operate in specifically designed environments to protect patients from COVID-19.

Research to identify systems to perform surgery safely despite the pandemic could help minimise future cancellations and reduce the impact on population health.

COVID-19 free Surgical Pathways

To continue to offer cancer surgery during the pandemic as safely as possible, some health systems and hospitals adapted their services to offer ‘COVID-19 free surgical pathways’. As redesign is expensive it must be supported by sound evidence. This study, the first data from the CovidSurg Cancer study, examines the rates of breathing complications, COVID-19 infection and death after surgery, in hospitals with specially designed pathways versus those operated without defined pathways. It has been published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

Context: Providing rapid treatment for cancer surgery is important to avoid worsening disease whilst waiting for an operation. COVID-19 has increased the risks associated with surgery. In some places, surgical units have been organised to strictly separate patients having surgery from areas where patients with COVID-19 are treated. These are known as COVID-19 free surgical pathways.

Aim: To measure how often patients get serious breathing complications after cancer surgery during the pandemic, depending on whether they are treated in a COVID-19 free surgical pathway or a hospital without this setup.

Impact: Healthcare providers can use this evidence, to invest in the right facilities, to continue to undertake operations and deliver care as safely as possible.

Strategy: We invited surgeons from hospitals worldwide to contribute to this study. 445 hospitals in 54 countries took part. Patients were included if they had surgery from the time COVID-19 arrived in that region until 19th April 2020. A COVID-19 free surgical pathway meant patients undergoing surgery were separated in operating theatres, critical care and inpatient wards, from areas of the hospital treating COVID-19. If any one area was shared with patients with COVID-19, the patient was considered to be treated in a unit with no defined pathway.

International team members collected anonymous patient data about age, gender, underlying illnesses, type of cancer and the operation. Patient records were followed up for 30 days after the operation. Researchers recorded if a patient had died or had been diagnosed with SARS-CoV-2 (severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, the virus which causes COVID-19) or one of three serious breathing problems: pneumonia (lung infection); unexpected ventilation (an artificial breathing machine); or acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS, where the lungs become badly inflamed and cannot provide the body with enough oxygen).

We expected that healthier (lower risk) patients would be treated more often in COVID-19 free surgical pathways, with fewer resources e.g. intensive care units. We tested the data to make sure the higher number of low risk patients treated within COVID-19 free pathways did not mislead our conclusions.

Results:

What did the study find?

9171 adults who had cancer surgery were included. 27% were operated within surgical pathways and 73% with no defined pathway. The patients operated within COVID-19 free pathways tended to be younger with fewer medical problems. Three quarters of all operations were major surgery.

- 2.2%, ~1/45 patients operated within COVID-19 free pathways had breathing complications.

- 4.9%, ~1/20 patients operated in a hospital with no defined pathway had breathing complications.

- Having an operation within a COVID-19 free pathway resulted in fewer breathing complications even after direct comparison of patients with the lowest risks from each group.

- SARS-CoV-2 infection was detected in 2.1% patients after an operation in a COVID-19 free pathway. This compares with detection in 3.6% patients following an operation with no defined pathway.

- 1.5% patients died within 30 days of their operation. Deaths were more common in patients with serious breathing problems and SARS-CoV-2 infection.

- Death rate was lower within COVID-19 free pathways.

Who is at highest risk?

Increased risk of breathing problems was identified among:

- Older patients

- Male patients

- Patients with other medical problems particularly with cardiac (heart) risks or existing respiratory (lung) disease

- Advanced cancer

- Patients undergoing major surgery

- High local levels of COVID-19

What else did we learn?

In the early phase of the pandemic only 27% of these patients had a SARS-CoV-2 test before surgery. With improved reliability of tests, screening will play a role to minimise operating on patients with asymptomatic or presymptomatic COVID-19. The benefits of COVID-19 free surgical pathways were greatest where there were high local levels of COVID-19.

Conclusion: Death after surgery was mostly related to serious breathing complications, which were high with post-operative COVID-19, and low in COVID-19 free surgical pathways. To protect patients, COVID-19 free surgical pathways should be used during this and future COVID-19 outbreaks to ensure planned cancer surgery can continue.

What about patients with previous SARS-CoV-2 infection?

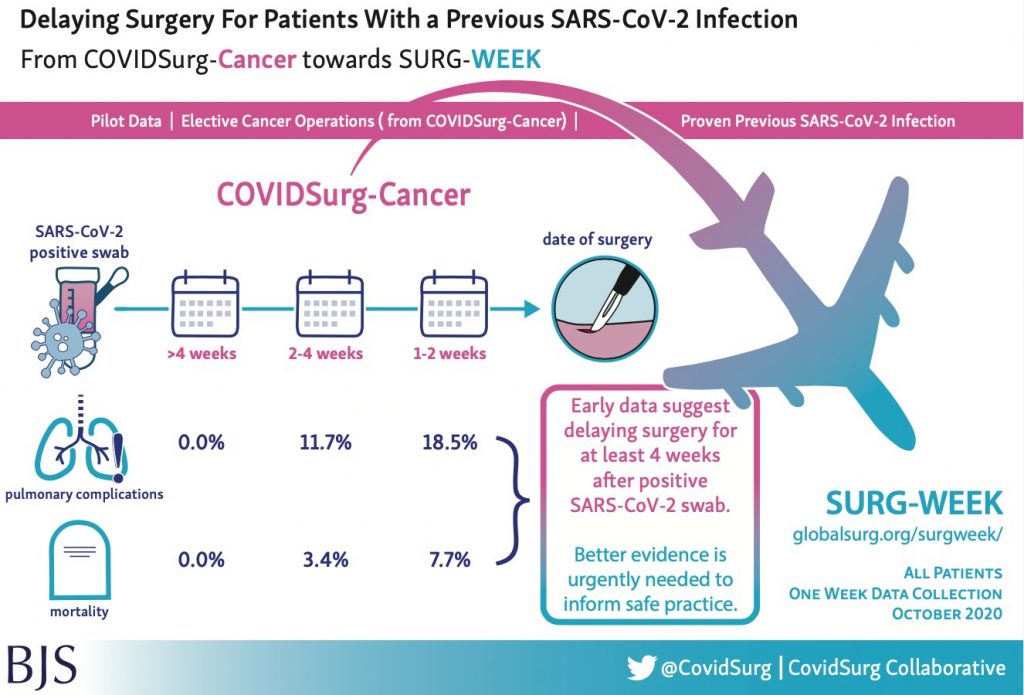

The first CovidSurg Cohort study results highlighted the dangers of having an operation and contracting COVID-19 around the same time. The data from the CovidSurg Cancer study allowed us to take an early look at a sample of patients having planned surgery with a previous positive SARS-CoV-2 swab. It was published as a letter in the British Journal of Surgery.

Context: Surgeons globally are working through a backlog of at least 28 million operations that were delayed during the first COVID-19 pandemic wave. Inevitably, many patients who have already been infected with the virus will need surgery. At present we don’t know when is the safest time to have an operation after SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Aim: To identify relationships between a previous positive SARS-CoV-2 swab and serious breathing problems after surgery.

Impact: Identifying the optimal timing for surgery following SARS-CoV-2 infection will help surgeons and patients plan surgery, protect patients and save resources.

Strategy: Patients undergoing planned cancer surgery during the pandemic up to 24 May 2020, with a previous positive SARS-CoV-2 swab were identified from the CovidSurg Cancer study data. Their data was compared to patients without previous positive swabs to explore their outcomes.

Results: Data came from patients treated in 78 different hospitals in 16 countries. 112 patients with a previous positive swab were matched with 448 patients with no previous positive swab. A higher rate of serious breathing complications occurred after operation in patients with previous infection. This was lower when the operation occurred > 4 weeks following a positive swab.

What does this mean?

The small number of patients with previous SARS-CoV-2 and the methods of matching in this study are imperfect, so these results are not conclusive. However they give an indication of the risks of previous SARS-CoV-2 for surgical patients.

Conclusion: Currently, for patients planning surgery, it is advisable to delay surgery at least 4 weeks from the time of a positive swab. Future, larger study data will try to establish the safest time for surgery after infection. To help guide surgical patients and healthcare professionals to understand risk, we hope to be able to examine differences between previous symptomatic and asymptomatic infections.

Testing for SARS-CoV-2 infection before surgery

As we continue in and between subsequent pandemic waves, and patients are booked for surgery, the CovidSurg Cancer study data can help to identify where services can best spend resources to protect patients. This paper, published in the British Journal of Surgery evaluates the associations between SARS-CoV-2 testing before operations and serious breathing problems afterward.

Context: At least 28 million operations were delayed during the first COVID-19 pandemic wave. As we resume operating, we need the ability to identify patients with pre-symptomatic infection and postpone surgery to keep those patients safe. We also need to use resources wisely by testing in situations where it will likely provide a benefit.

Aim: To understand the value of preoperative SARS-CoV-2 testing to prevent serious breathing problems after surgery.

Impact: To maximise the benefits for patients and guide the use of resources, this study looks at where and when swab testing can change patient outcomes.

Strategy: Surgical team members in 432 hospitals in 53 countries collected anonymised data for all patients having planned cancer surgery during the pandemic up to 19 April 2020. We included all patients with data about preoperative testing. Patients suspected of having the infection pre-operatively were excluded. Researchers recorded if a patient died or had serious breathing problems up to 30 days after their operation.

Results: 2303/8784 patients (23%) were tested for SARS-CoV-2 before their operation. 1458 had a swab test, 521 a CT scan of their chest and 324 had both tests. 6746 major operations and 1087 minor operations were performed in high SARS-CoV-2 risk areas and a minority of operations took place in low risk areas.

Overall, 4% of patients experienced serious breathing problems following surgery. The rate was higher in patients with no test or CT scan-only testing. At least one negative swab before operation reduced the risk of serious breathing problems after surgery. Having repeated swabs did not add extra benefit.

The data showed that swab testing reduced breathing problems in high risk COVID areas but not in low risk areas. It also showed that a swab before major surgery reduced breathing problems but not before minor surgery.

How many patients must be swabbed to prevent one patient having serious breathing problems?

To prevent one patient having serious breathing problems after major surgery, in a high risk area, 18 patients had to be swabbed; 48 had to be swabbed before minor surgery in a high risk area. This increased to 73 patients swabbed before major or 387 before minor surgery in low risk areas, to prevent one patient having breathing problems.

Some evidence also suggested there was a lower death rate among patients who were swabbed before their surgery.

Conclusion: The study group was able to recommend that ‘A single preoperative swab should be performed for patients with no clinical suspicion of COVID-19 before major surgery in both high and low risk areas and before minor surgery in high risk population areas’.

Swab testing before surgery is likely to benefit patients by identifying pre-symptomatic or asymptomatic COVID-19 infection prior to admission. A positive swab result triggers operation delay, protects patients from severe breathing problems after surgery and helps protect other patients from in-hospital infection. Swabs together with other strategies, should be used to protect patients from COVID-19 during hospital care.

Sharing our research accessibly means producing different media to communicate our results to ensure surgeons, hospitals and patients can all access the results to make decisions based on real data.

To view our video abstract please click here.

The British Journal of Surgery‘s Cutting Edge blog also published our lay summary here.

Timing for safe surgery after SARS-CoV-2 infection

The earliest CovidSurg studies showed that peri-operative SARS-CoV-2 infection results in excess death after surgery. The CovidSurg Week study examined the outcomes of >140,000 global patients in October 2020, to compare those with previous SARS-CoV-2 to those without prior infection. It again demonstrated that SARS-CoV-2 infection before surgery increased death rates but was able to identify how much time is expected to pass after infection, for the risks with surgery to return to normal. This data helps surgeons and health services offer the safest surgery possible.

The paper was published in the journal Anaesthesia.

Context: There are high global rates of SARS-CoV-2 infection and many more survivors. There is also a huge backlog of patients awaiting surgery. More and more frequently, patients who have had prior SARS-CoV-2 infection will need surgery, but so far there is no data to advise how long we should wait before operating to avoid excessive risk of breathing complications or death.

Aim: To identify the safest time to have surgery following SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Impact: This evidence will help surgeons and patients plan surgery, minimise complications and save resources.

Strategy: Surgical teams registered to take part from 1674 hospitals in 116 countries. All patients of that specialty, (e.g. gynaecology, ear, nose and throat or orthopaedic surgery) undergoing any type of emergency or planned surgery at participating hospitals during a 7 day period at each centre, between 5 October – 1 November 2020 were included. Prior SARS-CoV-2 infection status was recorded. Patients with diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection before surgery were classified as asymptomatic, symptomatic-resolved or symptomatic with ongoing symptoms. Timing of diagnosis was grouped as 0-2 weeks, 3-4 weeks, 5-6 weeks or 7 or more weeks prior to surgery. Death and breathing complications up to 30 days following surgery were reported. Patient factors such as age, sex, other medical problems, urgency and reason for surgery (benign, cancer, obstetrics or trauma) were collected.

We checked the data to include only planned surgery patients to ensure the data was not skewed by emergency surgery, and to include only patients with positive swab tests (to eliminate mis-diagnosis among patients diagnosed clinically).

Results: 140,231 patients were included in the study. 3127 (2.2%) patients had a previous SARS-CoV-2 diagnosis, the timing of that infection was;

- 36% 0-2 weeks,

- 15% 3-4 weeks,

- 10% 5-6 weeks,

- and 38% 7 or more weeks before surgery.

Most patients had no symptoms by the time of surgery. Overall 1.5% patients died within 30 days of surgery however if SARS-CoV-2 was diagnosed 0-2 weeks before surgery, the death rate was 4% and remained elevated until the patient group with infection 7 or more weeks before surgery (whose death rate had returned to baseline). The increased death rate with surgery within 7 weeks of infection could be seen in all age groups, patients with or without other medical problems and with minor and major surgery and with any surgical urgency.

What about the risk of breathing complications after surgery?

Breathing complications were also increased in patients having surgery within 7 weeks following SARS-CoV-2 infection but after 7 weeks, risk for most, returned to that of the baseline population i.e. the same as patients with no history of SARS-CoV-2 infection.

A minority of SARS-CoV-2 patients with ongoing symptoms continued to have a higher rate of breathing complications.

How does this help?

Patients, surgeons and anaesthetists can use this evidence in shared decision making about timing of surgery. Surgical delay must be balanced with the risk of disease progression, particularly in the context of aggressive cancer diagnoses.

Conclusion: Surgery after SARS-CoV-2 diagnosis should be delayed at least 7 weeks, where possible, to reduce the known risks of serious breathing complications and death. For patients with ongoing symptoms, a delay beyond 7 weeks until symptoms resolve may be beneficial.

Sharing our research accessibly means producing different media to communicate our results to ensure surgeons, hospitals and patients can all access the results to make decisions based on real data.

To view our webinar please click here, (presentation of this data from 26m:20s).

COVID-19 vaccination to reduce complications after surgery

This study explored the benefits of COVID-19 vaccination for patients waiting for elective (planned) surgery. The study found that vaccination could significantly reduce patients’ risk of dying after elective surgery. In addition, as the number of lives saved by vaccinating surgical patients would be larger than the number saved by vaccinating the general population, the study recommends that governments should consider prioritising vaccination for patients planned to undergo surgery.

The paper was published in the journal British Journal of Surgery.

Context: With limited global availability of COVID-19 vaccinations, it is important to prioritise patients who will likely have most benefit. This study calculated the benefits of vaccinating patients waiting for elective (planned) surgery. The study found that vaccination could significantly reduce patients’ risk of dying after elective surgery. In addition, vaccinating surgical patients would save more lives per 1000 vaccines than vaccinating the general population (not waiting for surgery), so the study recommends that governments prioritise vaccination for patients planned to undergo surgery.

Aim: To statistically model the benefit of COVID-19 vaccination for patients awaiting planned surgery using rates of post-operative SARS-CoV-2 and death in surgical patients compared with community SARS-CoV-2 infection and deaths rates.

Impact: This evidence can help health services and governments plan and prioritise the most effective use of vaccination resources.

Strategy: The study focused on patients having elective surgery with an overnight stay in hospital, collected in October 2020, before any COVID-19 vaccinations became available. It was based on data for over 56,000 patients (1,667 hospitals, 116 countries).

The patient data was used to compare the death rates in patients who were diagnosed with SARS-CoV-2 infection after surgery with patients who were not diagnosed with SARS-CoV-2. This was used to estimate how many lives could be saved by COVID vaccination among surgical patients compared with how many lives saved by vaccinating the general population (not waiting for surgery).

Results: Although many hospitals have introduced measures such as nasal swab testing and “COVID-free surgical pathways” (you may have seen these on the news described as ‘COVID-cold’, ‘COVID-green’ or ‘COVID-lite’ hospitals) which reduce risk of patients catching COVID-19 infection in hospital, these measures do not completely remove all risk. Some hospitals may not be organised in a way that it is possible to provide these measures.

This study found that globally between 0.6% and 1.6% of patients are diagnosed with COVID-19 infection after elective surgery.

Impact of COVID-19 infection on surgical patients

Patients who are diagnosed with COVID-19 infection after surgery have 4-8 times higher risk of dying compared to similar surgical patients who are not infected.

Benefits of vaccination for surgical patients

Rigorous previous studies have shown that most COVID-19-related deaths can be prevented by COVID-19 vaccination. This study found that surgical patients are at higher risk than the general population of being diagnosed with COVID-19 infection, and if they are infected, they are at higher risk of dying than someone in the community diagnosed with COVID-19 infection. This means that fewer surgical patients need to be vaccinated to save one life, compared to the general population.

In every age group fewer surgical patients need to be vaccinated to save 1 life than matched people in the general population. Patients over 70 years and those undergoing cancer surgery had the greatest benefit of vaccination. Specifically, 1,840 people aged 70 years and over in the general population need to be vaccinated to save one life, but only 351 in patients aged 70 years and over having cancer surgery.

Risks of vaccination

Vaccines are rolled out only after being rigorously tested for safety in order to gain government approvals for use in patients. Different vaccines are in use in different countries but all must first pass these strict safety checks.

What advice is there for patients who are waiting for surgery?

Patients waiting for surgery who have not yet had a COVID vaccine should discuss this with their surgeon. Patients may want to ask the following questions:

- Would I benefit from having my vaccine before my operation?

- What is my risk from COVID-19 infection around the time of surgery?

- Is it possible to delay my surgery long enough for me to have a complete vaccine course?

- Is it possible for me to be vaccinated, and if so, how do I go about this?

- How is my hospital trying to reduce the risk of me becoming infected with COVID-19?

How long before surgery should the vaccine be given?

Although this study did not investigate the best timing for vaccination before surgery, other studies have shown that the risk of COVID-19 infection is reduced from around two weeks after vaccination. We should aim to give the vaccine at least two weeks before the day of surgery, but a longer gap would be preferable.

Which vaccine and how many doses?

This study did not compare different vaccines and currently there is insufficient data to know which vaccines best protect surgical patients, so any of the COVID-19 vaccines may be used. It is preferable to have both doses of a two-dose vaccine prior to surgery but if it is only possible to give one dose within the timespan, this is better than having neither.

Conclusion and Recommendations for Government: Many countries, particularly low- and middle-income countries, will not have easy access to COVID vaccines for several years. While vaccine supplies are limited, most governments are providing vaccination to groups at highest risk of COVID-19 mortality first.

This study suggests that patients waiting for elective surgery should be offered COVID-19 vaccination ahead of other people of the same age and gender in the general population. Provision of vaccinations for all elective surgery patients could save an additional 58,687 lives worldwide over the next year.

Sharing our research accessibly means producing different media to communicate our results to ensure surgeons, hospitals and patients can all access the results to make decisions based on real data.

To view our webinar please click here, (presentation of this data from 04m:36s).

Elective cancer surgery during COVID-19 lockdowns

As we continue to navigate pandemic waves and varying levels of lockdown, safety measures have been put in place to offer patients COVID-safe surgery. But pressures from COVID-19 threaten surgical services, and cancellations impact care particularly time-critical cancer treatment. The CovidSurg cancer study has examined the resilience, and fragility, of surgical services particularly looking at the impact of lockdowns on surgical services and patient journeys.

By demonstrating the effect of lockdowns on surgical care, this study helps to identify how services may be bolstered to allow cancer surgery to continue in lockdown scenarios, it recommends protected surgical care beds including critical care provision and the workforce to staff services to minimise disruption.

This paper is published in The Lancet Oncology journal.

Context: Global lockdowns of different degrees have helped protect communities from SARS-CoV-2 transmission since early 2020. Their effects on health service performance is not yet well understood.

More than 20 million operations were cancelled globally in the first COVID-19 waves due to concerns for perioperative SARS-CoV-2 (infection with the COVID-19 virus around the time of surgery), and due to hospital capacity problems. National guidance promoted that time-critical surgery, including cancer surgery should continue. Most cancer patients need surgery (rather than other treatment) for a cure.

Aim: The study aimed to include every cancer patient in the early months of the pandemic, whose treatment decision was for operation, whether or not the planned surgery took place. By including both operated and non-operated patients and their outcomes, analysis of the whole system could take place.

Impact: The study highlights the fragility of surgical services to promote protection of elective surgical pathways to ensure delivery of cancer surgery in future pandemic waves.

Strategy: Patients with 15 solid cancer types who had a treatment plan for operation, from 466 hospitals in 61 countries were anonymised and enrolled in the study. For each patient a score (called the Oxford COVID-19 Stringency Index score) was calculated to describe the type of national lockdown restrictions that were in place during the time they waited for their operation.

Patients’ treatment was recorded and patients who did not undergo their planned surgery were examined to understand the links between lockdowns and non-operation.

Results:

What proportion of patients were not operated due to COVID-19?

20,006 patients (planned for cancer surgery), were enrolled in the study. Overall 1 in 11 patients did not undergo surgery after at least 3 months follow up due to a COVID-19 related reason. In fact, this was often much longer, with half of patients who waited over 3 months still not having had surgery at 16-30 weeks follow-up and a quarter still not operated after >30 weeks.

During full lockdowns, one in seven patients (15%) did not have their planned operation after five months from cancer diagnosis. COVID-19 was reported as the reason for these delays or cancellations. Moderate lockdowns led to one in eighteen patients not being operated (5.5%) and with lighter restrictions (close to usual services), fewer patients did not undergo surgery, at just 0.6% (approximately one in 200).

Patients with advanced cancer, frailty and in countries with low-resourced health systems were least likely to undergo their surgery.

For patients who were operated, how did COVID-19 affect the waiting time from cancer diagnosis to surgery?

Almost a quarter (23.8%) of patients with cancer diagnoses during full lockdowns experienced greater than 12 weeks delay to surgery (without other treatment in the meantime). This was less significant with light or moderate restrictions where around one in ten patients waited more than 12 weeks.

Was surgery less effective due to the delays?

The study did not find that more cancers were unable to be surgically removed after the delays, however longer term follow-up would be useful to understand if disease came back later.

Conclusion: Cancer surgery systems are vulnerable to the effects of COVID-19, particularly in lower income countries. Elective surgery services, particularly for cancer surgery that is time-critical, needs to be strengthened to avoid delays to care with future pandemics or lockdowns.

To enable sustainable safe surgery in pandemic situations, facilities including intensive care as well as nominated staff should be protected to deliver COVID-19-free elective surgery. Vulnerable, frail patients with advanced cancer will benefit most from such protection as it is likely that critical care provision limited their selection for operation. Protected surgical services should be designed in parallel with surge capacity plans for acute care delivery to enable both important aspects of healthcare to be delivered safely.

For patients who have experienced additional waiting times before surgery, health services should consider closer monitoring to detect any disease recurrence at the earliest opportunity.

Sharing our research accessibly means producing different media to communicate our results to ensure surgeons, hospitals and patients can all access the results to make decisions based on real data.

To learn more in our webinar and online learning, please click here.

Bowel cancer surgery during the first part of the pandemic

Previous CovidSurg Cohort and CovidSurg Cancer study papers have looked at the impact on patients of undergoing surgery during the COVID-19 pandemic, whether that was major/minor or elective/emergency surgery. However, this broad overview did not focus on different body systems nor address the specific risks linked with operating on individual organ systems. The CovidSurg Cancer study data was used in this paper to look at the impact of the pandemic on patients having bowel cancer surgery to identify specific risks surgeons should be aware of and to assist surgical services to plan for safe surgery within safe surgical pathways.

It was published in Colorectal Disease.

Context: The pandemic led to a large number of non-urgent operations being cancelled in an effort to reduce infection in patients who would have attended hospital. The pandemic also diverted equipment and people from their normal working environments to assist in the increased demand on intensive care facilities coping with COVID-19 patients.

Guidelines were published to guide surgeons to care for patients who required urgent surgery. These guidelines prescribed more risk averse types of operations to avoid the need for intensive care support afterward and reduce the risks of death if a complication did occur. One recommendation was to avoid creating bowel joins (anastomoses) after removal of a segment of bowel; instead stomas were recommended (openings of the intestine onto the abdominal wall to excrete poo). The purpose of this change was to reduce the possibility of a join leaking (causing patients to become very unwell, need further surgery and/or intensive care treatment and a significantly longer hospital stay).

Despite high risks of operating with the possibility of COVID-19 around the time of surgery, cancer surgery is time critical and had to continue even early in the pandemic. This paper helps to understand what happened to those patients.

Aim: To understand the impact of the pandemic on bowel cancer patients, specifically, changes in types of operation and death rates after surgery.

Impact: This data helps surgeons and hospitals understand risks to patients undergoing bowel cancer surgery during the pandemic. Understanding these risks can help services better protect patients from complications and provide safer surgery.

Strategy: The study included patients undergoing planned bowel cancer surgery during the pandemic up to 19 April 2020, with no suspicion of SARS-CoV-2 infection before surgery. We collected data about COVID-19 and other complications after surgery including death, to compare it with rates of complications in pre-pandemic patient groups.

Results: 2073 patients undergoing large bowel cancer surgery were included. They were treated in 270 different hospitals in 40 countries. 60% were men and the majority (69%) had mild or no other medical problems. Just under half (46%) of the bowel cancers were in the rectum (last part of the large bowel) and most (63%) cancers were stage I-II (cancer had not spread to other organs). 38% operations were performed ‘open’ (through a big cut) and 62% through keyhole or robotic techniques but 5% had to be changed to open surgery afterward.

Were more stomas created?

Stomas were created more often (34% vs. 27%) than before the pandemic. However just 90/708 stomas were reported to be made due to COVID-related change in decision making. Stomas were created more often for patients with cancer of the rectum. Anastomoses (joins) without a stoma (to divert stool until the join heals), were made less often. Surgeons most commonly reported that professional guidelines and the need to avoid complications that might need intensive care support were the reasons to change practice and create a stoma.

How many patients died?

2% (38) patients died after their bowel cancer surgery, within 30 days. Death was more likely with SARS-CoV-2 after surgery and anastomotic (join) leak. 4% patients developed SARS-CoV-2 infection after their surgery and 5% suffered anastomotic (join) leak. Very few patients developed SARS-CoV-2 and an anastomotic (join) leak, but when both of these complications occurred, the chance of death increased hugely (38%) and 5 out of 13 patients died. Whereas, in patients without a leak or SARS-CoV-2, only 0.9% died (14 out of 1601). Patients who died were more often male, over 70 years, with advanced cancer and having more extensive surgery.

Conclusion: This study shows that there was just a small change in rate of stoma creation early in the pandemic. More importantly, it has highlighted the need to protect patients from SARS-CoV-2 infection after surgery and from anastomotic leak, both of which were associated with high risk of death after surgery. Hospital teams are working to optimise their surgical pathways to protect patients and can use this data to support investment to keep patients safe.

We shared the results from patients undergoing colorectal surgery in the early months of the pandemic in a webinar you can view here.

Sharing our research accessibly means CovidSurg produce different media to communicate to surgeons, hospitals and patients so they can all access the results to make decisions based on real data.

COVID-19-related absence among surgeons

COVID-19-related absence among surgeons includes sickness, self-isolation, shielding, and caring for family members. To estimate the amount of surgery possible during a pandemic surge, the CovidSurg team called on experts – senior surgeons, in March-April 2020, to determine the minimum surgical staff required to provide emergency surgical services while maintaining different proportions of elective surgery.

The results will inform surgical service planning during future COVID-19 outbreaks. In most settings, surgeon absence is unlikely to be the factor limiting elective surgery capacity.

It was published in BJS Open.

Context: The initial phases of the COVID-19 pandemic strained surgical teams globally. Surgeons cancelled operations and redeployed staff to help the COVID-19 response in other hospital areas.

Significant surgeon absence is expected as surgeons may be more likely to get the virus due to exposure to contaminated tissues and droplets in theatre. A further proportion will also need to self-isolate (if they or a member of their household has symptoms), shield (due to other medical problems or pregnancy) or undertake caring commitments.

Aim: To detect the global absence rates of surgical team members and create a formula to predict the amount of planned (elective) surgery possible during future pandemic outbreaks.

Impact: A predicted model of absence will enable surgical teams to plan the services that may be continued during future pandemic outbreaks while still offering team members to move departments and help other areas of the hospital.

Strategy: An international network of surgeons contributed real-world COVID-19 surgical team absence rates. A select group of expert surgeons also reported the minimum number of staff required to run emergency surgery services alone and the number needed to continue planned surgery at either 25, 50 or 75% usual amount in small, medium and large surgical units.

Results: 451 surgeons in 364 hospitals from 65 countries responded, reporting surgical team absence rates of 20-25% during the first 6 weeks of the pandemic, then falling to 9-14% in the next 6 weeks.

Based on these expert surgeon estimates, and even with high absence rates, it appears possible to continue at least 75% of usual planned surgery during future pandemic waves. These figures still allow redeployment of some colleagues to help with direct COVID-19 patient care.

What should we keep in mind?

This study uses estimates made during the first COVID-19 outbreak. Measures such as social distancing and increased testing availability affect isolation periods and lockdowns. These in turn affect childcare commitments, the likelihood of surgeon infection and will influence surgeon absences in future outbreaks. Rota adaptations may also alter the number of staff required during an outbreak.

Conclusion: In future COVID-19 outbreaks at least 75% of planned surgery can continue, based on expected surgical team staffing levels. In most settings, elective surgery capacity will not be limited by absent surgeons. There will still be availability for some redeployment to help other parts of the hospital such as critical care. Forward-planning should help operations continue and minimise further deterioration in population health caused by mass cancellations of surgery.

Making an Impact

Our aim is to protect patients by making data driven decisions and sharing our research results to generate greatest patient benefit. To create this impact we have used multimedia to share our results with surgeons and anaesthetists, patients and healthcare services.

You can follow our work on Twitter @CovidSurg.

CovidSurg’s patient information about having surgery during the COVID-19 pandemic is directly informed by our research and co-produced with patient advisors. It is easily accessible to patients and clinicians worldwide in our Patient Resources webpage.

On behalf of the CovidSurg Collaborative, the CovidSurg Patient and Public Involvement team with patient advisory group member Carrie Tierney Weir, co-authored an article about how we co-produced patient resources to share brand new research results in a matter of weeks, under lockdown conditions and in multiple accessible formats. You can read it in The BMJ Opinion or The BMJ here: Surgery during covid-19: co-producing patient resources.

The CovidSurg group, a huge collaborative network, has a strong base in trainee surgeons. Training has been severely impacted by the pandemic but trainees are adaptable and the pandemic has opened up opportunities for development in other disciplines – surgical innovation, research, leadership, online teaching (and online learning). Much innovation has been borne from this global crisis, and as we learn to live with constant change, the ability to be flexible and resourceful will be valued.

Surgical trainee Elizabeth Li and Academic Foundation Doctor Emily Mills described in the Royal College of Surgeons’ Trainees’ Bulletin how the COVID-19 pandemic has affected surgical training and what strategies can be used to take best advantage of the continuing opportunities in surgical training.

Planning for the Future

The CovidSurg Cancer study has assessed the safety of surgery for all types of cancer in different hospital environments during the COVID-19 pandemic. Further results will shortly be published.

A study looking at the impact of COVID-19 on the surgical workforce so services can be better prepared for any future outbreaks is also soon to be published.

Thank you Video

This video contains the early results from CovidSurg data and thanks our funders.

If you are interested in watching more detailed results you can watch the CovidSurg webinars here.

More Details

This work is dedicated to every patient we lost, but whose data has made research possible.

And second, to the healthcare workers who strived to save those patients but who were lost too.

These summaries have been prepared by a team of colleagues including Lesley Booth, Chetan Khatri, Karolin Kroese and Elizabeth Li.

The Research Explained venture has been led by Mary Venn and all work has been approved by our Patient Advisory Group.

Funding: The CovidSurg publications were funded by a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Global Health Research Unit Grant (NIHR 16.136.79) using UK aid from the UK Government to support global health research; Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland; Bowel & Cancer Research; Bowel Disease Research Foundation; Association of Upper Gastrointestinal Surgeons; British Association of Surgical Oncology; British Gynaecological Cancer Society; European Society of Coloproctology; NIHR Academy; Sarcoma UK; Vascular Society for Great Britain and Ireland; Yorkshire Cancer Research. The funders had no role in study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation, or writing of the reports.